Overview

The Open/Closed Principle (OCP) is one of the fundamental principles of object-oriented design, forming part of the SOLID principles. The concept is simple: “Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification.” This principle encourages building systems where new functionality can be added without altering existing code. This leads to more maintainable, scalable, and robust software.

In this article, we will explore the Open/Closed Principle and how to apply it in Swift through examples, focusing on the Decorator Pattern to extend behavior without modifying the original code.

What is the Open/Closed Principle (OCP)?

The Open/Closed Principle (OCP) states that:

- Open for Extension: A class or module should be designed in a way that allows it to be extended with new behavior without modifying its existing code.

- Closed for Modification: Once a class or module is created, it should not be altered directly. Any changes or new functionality should be added in a way that preserves the original structure and behavior of the class.

In simpler terms, OCP promotes extending an object’s functionality by adding new classes or methods, rather than modifying the existing ones.

How to Apply OCP in Swift?

Swift offers powerful features like protocols, extensions, inheritance, and polymorphism that can be leveraged to implement OCP in a clean and effective manner. One way to implement the OCP in this case, is using protocol and Decorator.

Example: Applying OCP with Protocols and Decorators

Consider a scenario where you have a ChapterLoader protocol that loads chapters for a book. You also have a class RemoteChapterLoader that fetches chapter data from a remote server. Now, let’s say you want to add logging to this process without modifying the RemoteChapterLoader.

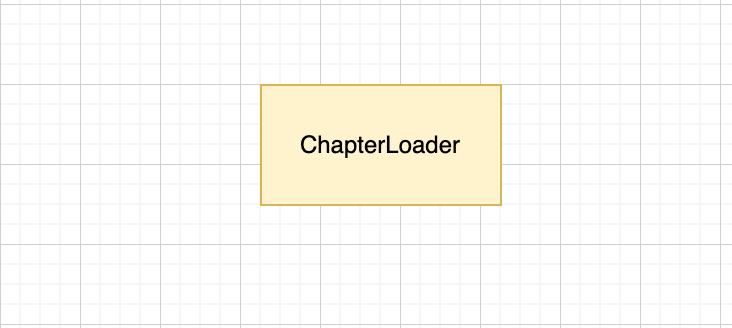

Step 1: Define the ChapterLoader Protocol

protocol ChapterLoader {

func load() async throws -> [ChapterEntity]

}

In this part, we will only have one component at least, the protocol.

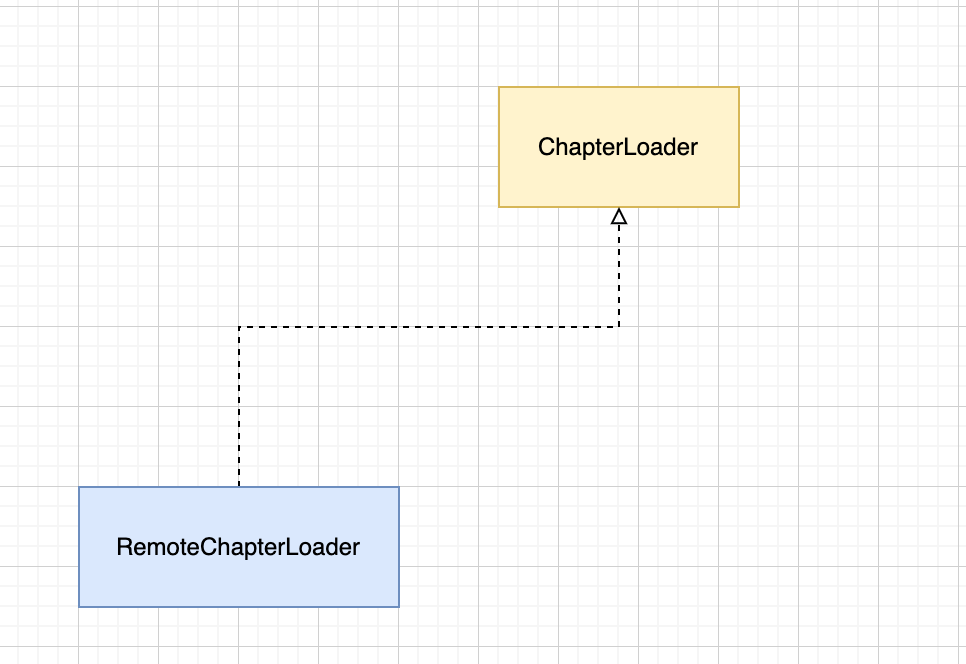

Step 2: Implement a Concrete Class (RemoteChapterLoader)

struct RemoteChapterLoader: ChapterLoader {

private let client: any HTTPClient

// ...

func load() async throws -> [ChapterEntity] {

let data = try await client.get(from: Self.url)

guard !data.isEmpty else {

throw Error.invalidJsonData

}

return try await map(from: data)

}

private func map(from data: Data) async throws -> [ChapterEntity] {

let response = try JSONDecoder().decode(LoadChapterResponse.self, from: data)

return response.chapters.map { $0.toChapterEntity() }

}

}

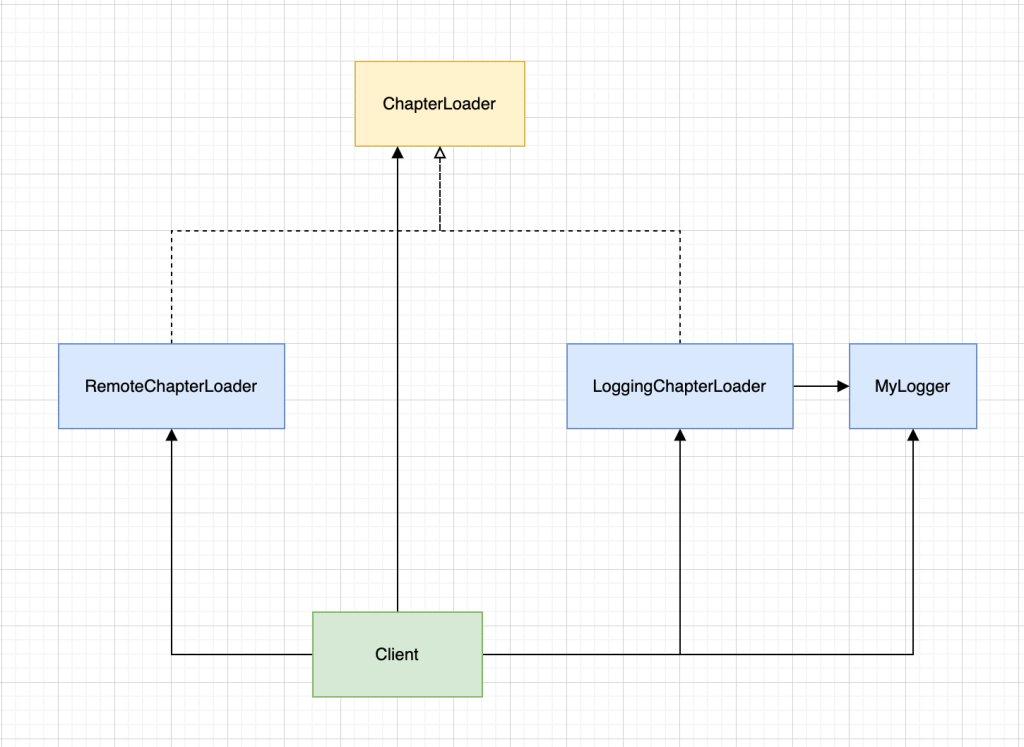

Now, since we add RemoteChapterLoader that conforms to ChapterLoader protocol, we will have such shape in the diagram :

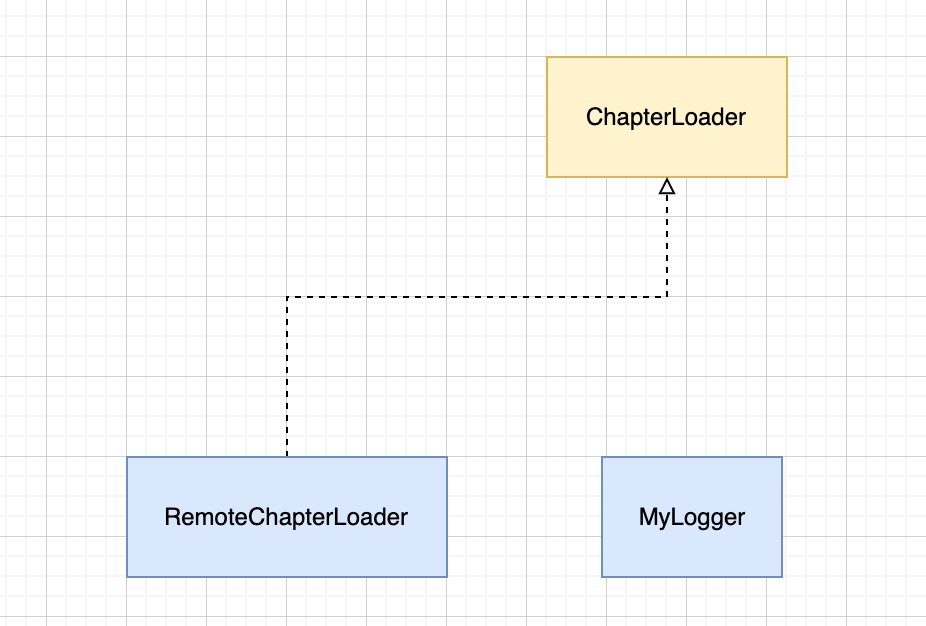

Step 3: Create a Logger (MyLogger)

struct MyLogger {

func log(message: String) {

print(message)

}

}

Now, we created a new component MyLogger so that it will be used with the Decorator (which align with the Open Close Principle).

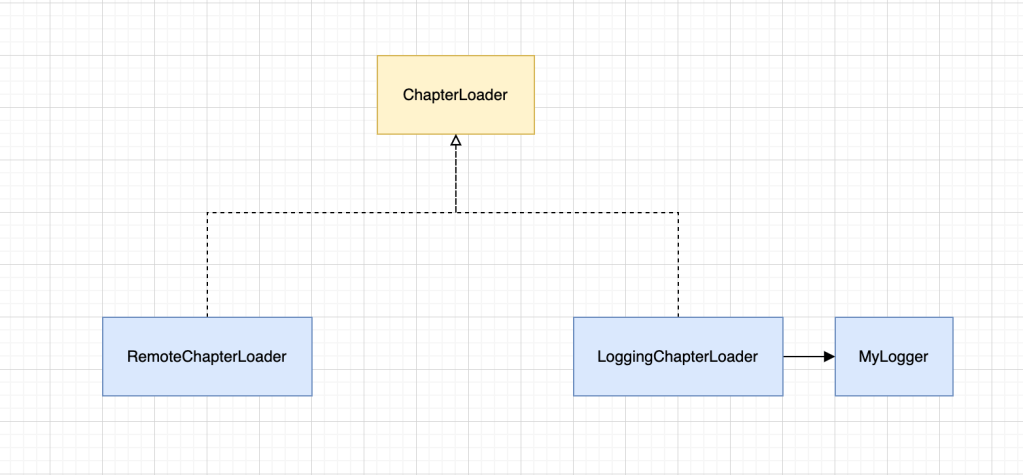

Step 4: Add a Decorator (LoggingChapterLoader)

struct LoggingChapterLoader: ChapterLoader {

private let decoratee: any ChapterLoader

private let logger: MyLogger

init(decoratee: some ChapterLoader, logger: MyLogger) {

self.decoratee = decoratee

self.logger = logger

}

// This is when Open Close Principle shine

func load() async throws -> [ChapterEntity] {

logger.log(message: "Loading chapters...") // Add additional behavior here

return try await decoratee.load() // keeping the old behavior

}

}

Right now, since we creates the decorator, we add another relationship in the dependency diagram.

In this example:

- The

RemoteChapterLoaderclass remains unchanged, fulfilling theChapterLoaderprotocol and loading chapters from a remote server. - The

LoggingChapterLoaderclass decorates the RemoteChapterLoader, adding logging functionality before delegating the actual work to the originalRemoteChapterLoader.

Step 5: Instantiation

let httpClient = SomeHTTPClient()

let remoteLoader = RemoteChapterLoader(client: httpClient)

let logger = MyLogger()

let loggingLoader = LoggingChapterLoader(

decoratee: remoteLoader,

logger: logger

)

Finally, the client, which a place on the codebase that ask the decorator instance, the LoggingChapterLoader, will need to communicate with all of the needed components.

The code is open for extension because we can add more decorators (like caching, retry logic, etc.) without altering the RemoteChapterLoader. It is also closed for modification because the RemoteChapterLoader class itself is not modified; instead, it is wrapped and extended via decorators.

Why OCP Matters

- Maintainability: When your classes adhere to OCP, adding new functionality is straightforward and doesn’t require changing the existing code. This reduces the chances of introducing bugs in well-tested code.

- Scalability: As your project grows, you can continue adding new behavior (like caching, retry logic, logging) to existing components without modifying their internal logic.

- Flexibility: OCP promotes a flexible system where classes and components can be reused and extended without disrupting the entire codebase.

- Testability: with this pattern, we can test the logging behavior easily and separately, usually using spy collaborators (or in some cases we call it call count)

Conclusion

By following the Open/Closed Principle (OCP), you ensure that your Swift code is designed for long-term success. The Decorator Pattern is one of the most effective ways to implement OCP, allowing you to extend functionality without modifying the original behavior of your objects. This approach leads to cleaner, more maintainable, and extensible code.

In summary, always strive to design your systems in a way that they are open for extension but closed for modification. Use protocols, inheritance, and patterns like decorators to create a robust and flexible architecture in Swift.